School leadership matters. Principals matter. School leadership, specifically principal leadership, is critical to the success of our nation’s schools, teachers, and students. Very few professions offer the vast opportunities to influence the lives of so many and leave a forever impact on those they serve.

However, school leadership is complex. School leadership is messy. School leadership is hard. Arguably, the principalship is the most challenging position in education. But even with its complexity and messiness, it is the “hard” about school leadership that makes it so important. It is the “hard” about school leadership that makes the profession so great. Otherwise, anyone could do it.

In order to help school leaders effectively navigate the impact, complexity, and messiness of their work, we, a group of state principal associations known as the School Leader Collaborative, look to re-conceptualize how we view principal leadership with a framework we call the School Leader Paradigm. What makes the School Leader Paradigm, or the Paradigm for short, unique is that it not only details the work principals must be doing within their learning organizations, but it also accounts for how principals must be personally invested in developing their own leadership competencies and attributes to become learning leaders.

In the sections that follow, we offer an overview of school leadership’s critical importance. Further, we highlight a serious problem of practice in our profession along with our theory of action for how to tackle it. Finally, we lay out the elements of the Paradigm and how we will use it to guide our efforts to support our nation’s principals.

School Leadership Matters

“Everything rises and falls on leadership,” according to leadership guru Dr. John Maxwell in his book The 21 Indispensable Qualities of a Leader.2 Maxwell’s claim is reinforced by Jim Collins’s research, which provided the basis for his best-selling book Good to Great. In his quest to determine what made good companies great, Collins identified the now well-known concept of Level 5 Leadership. According to Collins, Level 5 leaders “build enduring greatness through a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.”3 Something fascinating about Collins’s research for Good to Great was the contrarian point of view he took regarding leadership and great companies. While studying high-performing organizations, Collins gave his research team instructions to downplay the role of chief executives to avoid what he felt was overly simplistic thinking about how the leader was responsible for the success or failure of a company. In the end, the data won out. Leaders matter.

Like great companies that need high-quality executive leaders, great schools need high-quality principal leaders. According to the Wallace Foundation in their 2009 report, Assessing the Effectiveness of School Leaders: New Directions and New Processes, Wallace recognized:

Effective leadership is vital to the success of a school. Research and practice confirm that there is a slim chance of creating and sustaining high-quality learning environments without a skilled and committed leader to help shape teaching and learning.4

Several studies backup Wallace’s claim, noting school leadership as sitting second to classroom instruction as a primary driver for student performance, both positive and negative.5 In particular, the body of research indicates principals have the greatest impact on student achievement in schools with the greatest needs (i.e., high poverty rates, low student attendance, low graduation rates, and high teacher turnover).6 Furthermore, principal leadership is the most important factor for attracting and retaining quality teachers.7 Research indicates that the main reason teachers choose whether or not to stay in a particular school is the quality of support they receive from their principal.8 Overall, schools require principals who are capable of collaboratively crafting a vision for student success, cultivating a student-centered culture, building others’ leadership capacity, improving instruction, and leading school improvement efforts.9 Essentially, effective principals lead effective schools.10

Our National Problem of Practice

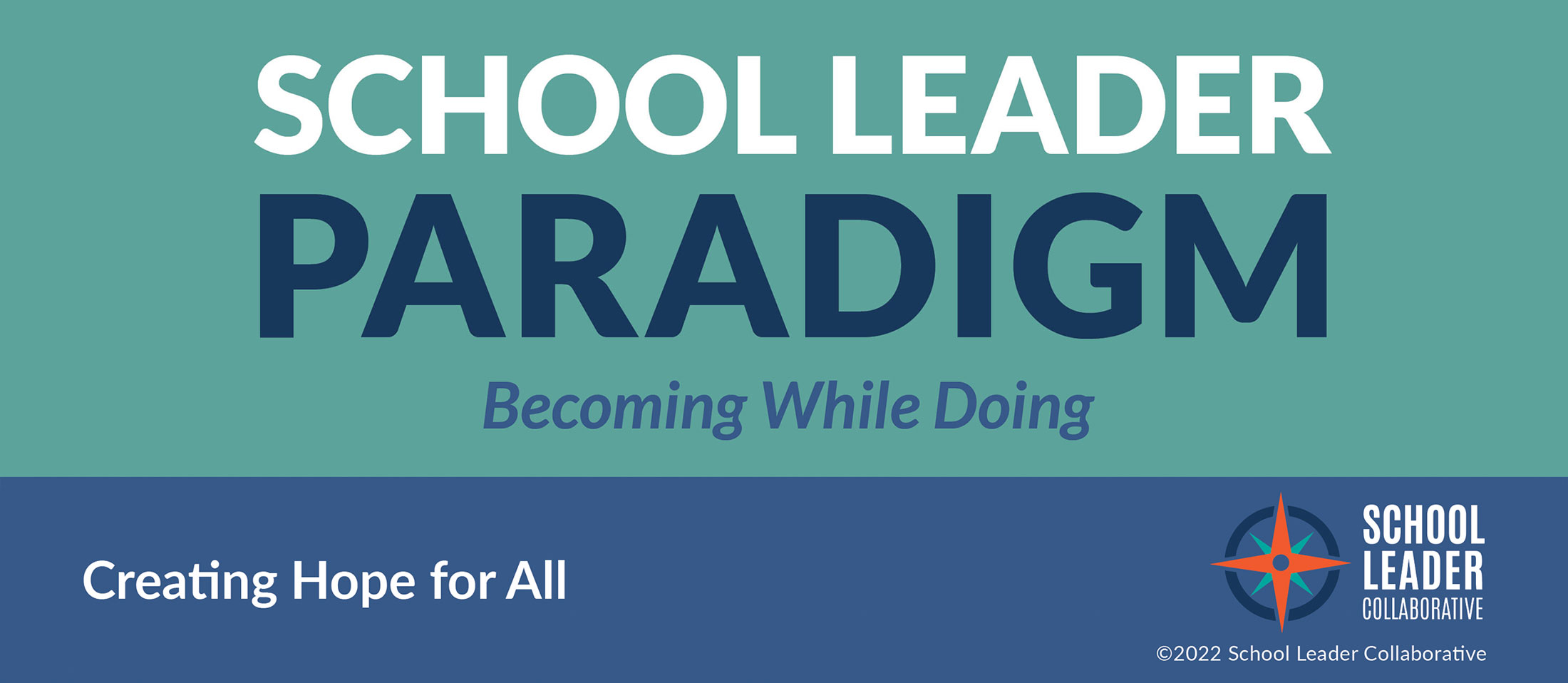

Only one out of four principals are in the same building after five years. This high turnover rate of building principals is costly in dollars, time, relationships, and—most importantly—impact on student learning.

While developing student-centered cultures as well as attracting and retaining high-quality teachers are critical strategies for school leaders to improve their schools, there is another essential element principals must possess: time. Typically, creating meaningful and lasting change in a school is equivalent to turning an oil tanker. For example, research tells us it takes 5 to 10 years for a principal to have a meaningful impact on a large school.11 Thus, school leaders need sufficient time to get the job done. Unfortunately, they do not often get it.

According to the School Leaders Network, only 1 in 4 principals stay in a given leadership position longer than 5 years.12 Of those that are brand new to the principalship, fifty percent do not make it past year three. Although some principals get promoted to the district office or take other building level positions, long hours, tough political environments, mounting mandates, rising expectations, shrinking resources, and narrowing pay with teachers push many promising principals out of school leadership altogether.13

Besides losing talented people from the profession, the costs of principal turnover are high both in terms of real dollars and its effect on learning environments. For example, preparing and onboarding a new principal carries an average price tag of $75,000 nationally.14 Furthermore, student performance in math and English language arts falls the year after a principal leaves, with the next principal needing up to three years to make up the loss.15 Where overall school climate is concerned, it is not uncommon to hear a veteran teacher utter the phrase “this too shall pass” when learning of an initiative introduced by yet another new principal. Even if the initiative is based on sound research, is there any doubt as to why the veteran staff member turns cynical since he or she has become accustomed to the coming and going of one initiative after the other with the coming and going of one principal after the other?

Our Theory of Action

In order to battle teacher cynicism, keep student performance on a positive trajectory, and save school districts’ needed resources, a two-prong approach of supporting principals must be taken: 1) increase their longevity in the schools they have been hired to lead; and 2) accelerate their effectiveness as school leaders. As outlined previously, the reason for this two-prong approach is fairly clear. Principals must have time to create positive, lasting change in their schools. However, since most principals do not benefit from the time needed to transform their buildings, they must be provided support to get better faster.

To this end, principals require robust preparation as well as rigorous induction, mentoring, and ongoing professional development throughout their career, not just the first couple of years.16 Furthermore, school leaders must be given autonomy to do their work, support with difficult decisions, and assurance when taking calculated risks that may fail.17 Additionally, principals should be allowed to connect with their peers, commonly known as professional learning networks, to learn from each other, offer encouragement, deliver constructive feedback, and, from time-to-time, provide collegial accountability.18

For school leaders to account for their own growth and for principal preparation programs, school districts, principals’ associations, and other organizations to be able to provide school leaders the critical support they need over the course of their careers, all must account for the complex nature of leadership and leading learning organizations. However, much of what is currently written or discussed about expectations for principals is a desire for them to be instructional leaders. This is a logical thought, but the term instructional leader is usually ill-defined or misunderstood. Too often, when people think instructional leader, a narrow vision of a principal sitting in a classroom observing teachers comes to mind. No doubt, principals need to spend time with teachers and students in classrooms, but capitalizing on opportunities to positively impact adult and student performance in schools demands much more. Instead of thinking of principals as just instructional leaders, we regard principals as learning leaders leading learning organizations.19 We know. It is a bit of a mouthful. Nonetheless, this concept more accurately describes who principals are and what they do, which necessitates a more comprehensive view and understanding of school leadership.

The School Leader Paradigm

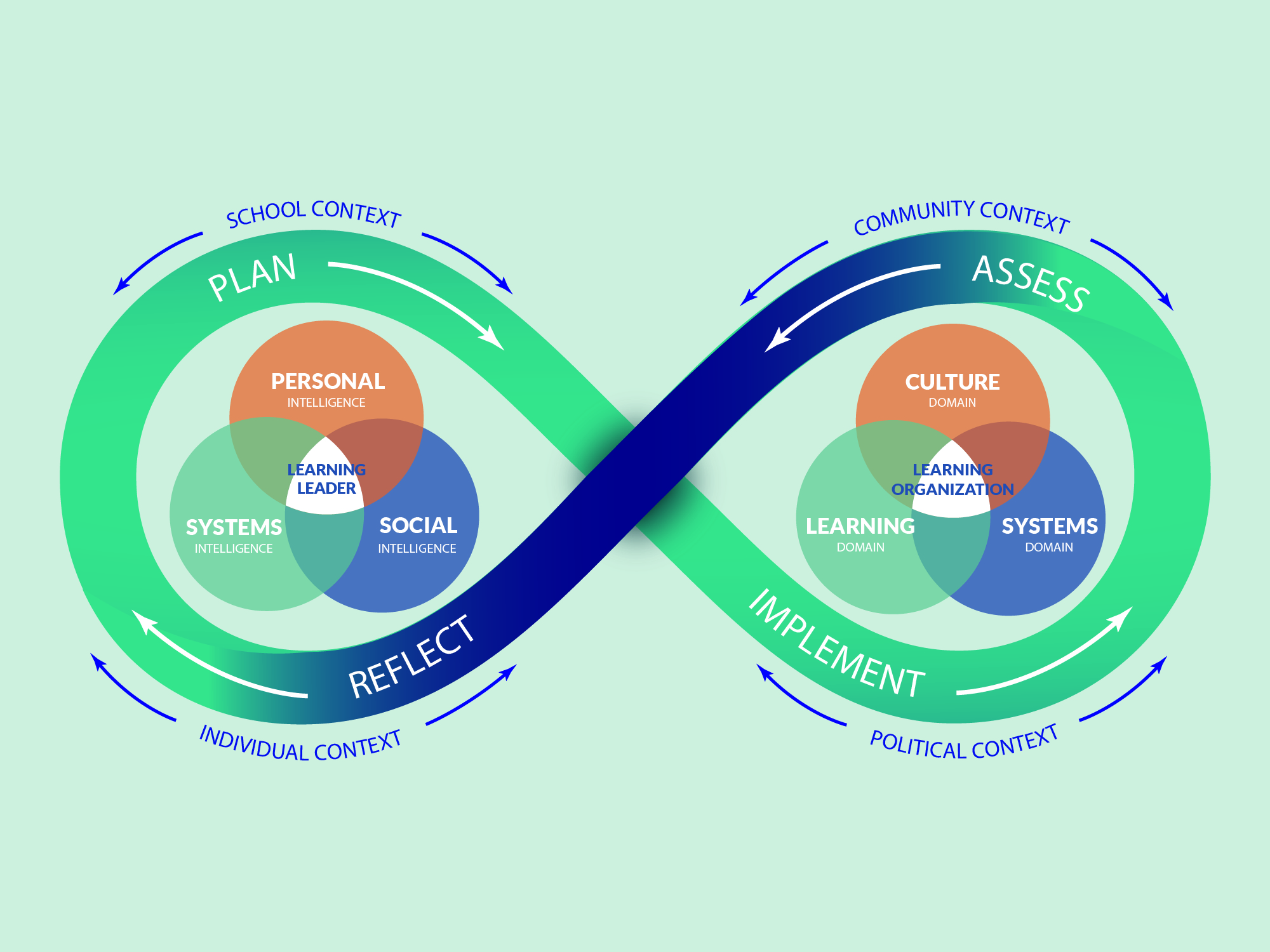

In order to provide a complete picture of principals as learning leaders leading learning organizations, we developed the School Leader Paradigm (see graphic above). The sections that follow break down the parts of the Paradigm and provide an explanation of each. Before digging in, though, you may be asking yourself, “What is meant by the concept of becoming while doing?”

From our experience and expertise, becoming while doing represents the art of school leadership. Specifically, we argue that principals, or learning leaders, should always be simultaneously improving their own leadership dispositions, or becoming, while doing the work of moving their learning organizations forward. Being totally self-aware and constantly reflective of the leadership intelligences (becoming) increases principals’ effectiveness to lead culture, systems, and learning (doing). Being cognizant of the interplay between becoming while doing is crucial for principals throughout their careers in whatever schools they lead. The content below provides the critical elements principals must account for in order to be becoming while doing, which results in positive outcomes for them, their organizations, their teachers, and ultimately their students.

The Infinity Loop

By shaping the Paradigm with an infinity loop (see graphic above), we suggest that the influence and impact of a school leader is eternal, going on, well, forever. Principals may come and go, but the influence they have on others while leading their schools reverberates always. Additionally, the infinity loop accounts for the two sides of leadership: 1) the leader; and 2) the organization the leader leads.

While the leader and the organization can be described separately, the two are inextricably connected, like two sides of the same coin. Lastly, the infinity loop signifies the state of continuous improvement both the learning leader and the learning organization must be engaged in to do what is best for their students. Thus, we embedded a cycle of inquiry within the infinity loop which we will discuss later.

Becoming

The popular leadership saying goes, “A leader is one who knows the way, goes the way, and shows the way.” In other words, leaders, including principals, must lead themselves well first in order to provide effective leadership for their schools. By establishing themselves as learning leaders, principals model the behavior they expect from both the adults and students in their learning organizations. Furthermore, principals gain credibility for their efforts by not requiring their followers to do something they are not willing to do themselves.

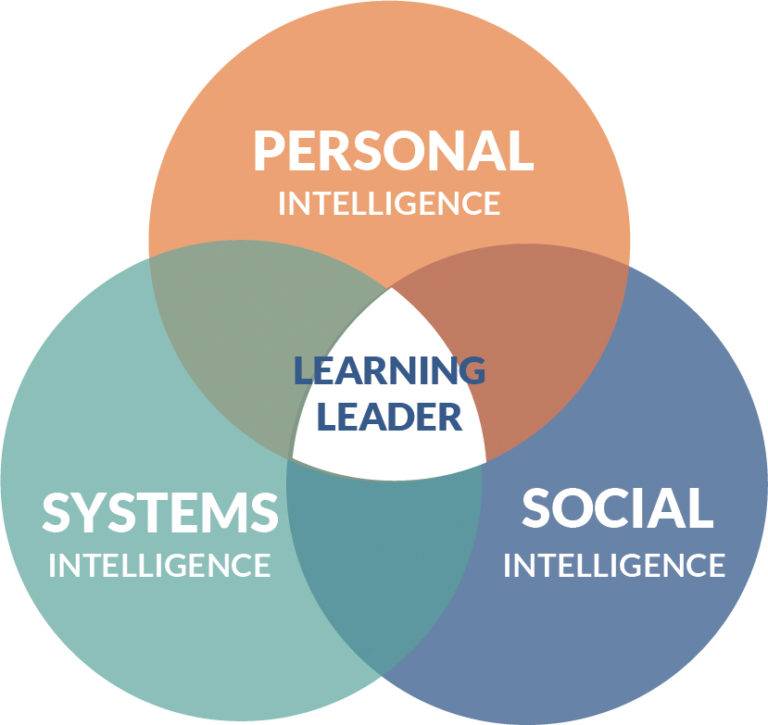

In order for a principal to become a learning leader, it requires the principal to possess a convergence of personal, social, and systems intelligences, as shown on the left side of the Paradigm. We use the term “intelligence” within the Paradigm in order to describe the ways principals need to be smart about their leadership. The intelligences are interconnected, do not act in isolation, and take into account the personal, social, and systems aspects of school leadership. Furthermore, intelligence implies how learning and growth, or becoming, need to take place for principals to become better leaders. The concept of “either you have it or you don’t” does not apply here. Improvement is possible even if it requires intentional, incremental growth, as is often the case when creating new habits and skills.20

To flesh out the intelligences on the becoming side of the Paradigm, we identified critical competencies and attributes principals must account for when working to grow, or become, as school leaders. While the entire becoming side of the Paradigm (including intelligences, competencies, and attributes) can be found in Appendix A, the definitions of the intelligences and their corresponding competencies are provided below.

As referenced previously, we believe principals must be in a perpetual state of self-actualization, which can be accomplished in part by focusing on the personal, social, and systems intelligences of school leadership. However, the intelligences with the corresponding competencies and attributes are not enough. School leaders must be able to concretely demonstrate their expertise by actually doing the work, which takes us to the other side of the Paradigm.

A detailed list of references used in developing the intelligences can be found here.

Personal Intelligence

The capacity of the principal to reason about personality and to use personality and personal information to enhance one’s thoughts, plans, and life experiences.21 The personal intelligence competencies include:

Wellness – Balances quality or state of being healthy in body and mind as a result of deliberate effort;

Growth Mindset – Embraces challenges; persists despite obstacles; sees effort as a path to mastery; learns from criticism; is inspired by others’ success;

Self-Management – Monitors and takes responsibility for one’s own behavior and well-being, personally and professionally; and

Innovation – Introduces new methods, novel ideas, processes or products that are put into operation.

Social Intelligence

A principal’s set of interpersonal competencies that inspire others to be effective.22 Social intelligence competencies include:

Service – Assures that other people’s highest priority needs are being served;

Community Building – Instills a sense of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together;

Capacity Building – Employs leadership knowledge and skills necessary to enable the school to make better use of its intellectual and social capital, in order to adopt high-leverage strategies of teaching and learning; and

Influence – Can cause changes without directly forcing them to happen; practices skills of networking, constructive persuasion and negotiation, consultation, and coalition-building.

Systems Intelligence

A principal’s understanding of the inner-workings and leadership of complex systems within a their learning organization.23 Systems intelligence competencies include:

Mission, Vision, and Strategic

Planning – Defines the mission as the intent of the school; fosters a vision of what the school will look like at its peak performance; strategically determines the procedural path to intentionally achieve the vision;

Operations and Management – Utilizes a variety of methods, tools, and principles oriented toward enabling efficient and effective operation and management;

Teaching and Learning – Develops and supports intellectually rigorous and coherent systems of curriculum, instruction, and assessment to promote each students’ academic success and well-being; and

Cultural Responsiveness – Promotes cooperation, collaboration, and connectedness among a community of learners while responding to diversity, need, and capacity.

Doing

What is principaling? Or, in other words, what is it that principals should be doing? Over the last few decades of education reform, this question has been more and more difficult to answer. The role of the principal has exponentially expanded to include responsibilities that did not traditionally fall under the purview or direction of the principal.24 We can argue as to the multitude of reasons why the role has changed over the years, but that will not help us define the current state of principaling in today’s schools. We can, however, identify one main influence contributing to the gradual increase on the workload and responsibilities for principals: the increased accountability legislated into the system from No Child Left Behind (NCLB), and subsequent legislation including the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Simply stated, our educational system prior to NCLB was designed to select, sort and remove students. NCLB ushered in a new era that held the system accountable to ensure that all students were successful, and that students would no longer be sorted out of the system.25

What did that mean for principaling? A massive paradigm shift occurred as principals moved from managers of schools to leaders of systems required to ensure the success of all students.26 What was generally acceptable in terms of school culture, systems, and learning outcomes was no longer permissible. Historically inequitable systems that perpetuated access and opportunity gaps for underserved and underrepresented students required immediate dismantling. Adult-centered systems that contributed to ongoing student failure, chronic absenteeism, high suspension rates, consistently low graduation rates, and institutional racism needed to be addressed in order to meet the requirements of NCLB.27

This mandated accountability system required new and unprecedented leadership from building principals. They (principals) could no longer just manage, but rather lead. Principals were charged with eliminating achievement gaps which required redefining a school’s culture, the systems that supported that culture, and how learning was defined for all stakeholders.

Now, the responsibilities and expectations of principals promulgated by NCLB persist with ESSA.28 What we know about principaling today is that it takes time for principals to change a school’s culture, build systems that support the culture, and nurture the ongoing learning of all stakeholders.29 The process does not happen overnight, nor in the first year.

From our work with school leaders, we know a principal new to his or her position invests the first few years establishing trust and building relationships in order to begin shaping the climate, then culture. Once high levels of trust and strong relationships have been built, the principal can then begin dismantling ineffective and/or harmful systems while concurrently creating improved systems that support a new culture. Over time, as the culture grows, and systems support that culture, then the principal tactfully and concurrently pushes on student and adult learning. We refer to this process as leading the convergence of culture, systems and learning. The art of leadership is balancing becoming a leader while guiding this convergence. A more veteran and experienced principal has the ability to accelerate the convergence of these domains concurrently, while a newer principal needs more time and tends to work from culture to systems to learning.

Simply stated, culture sets the foundation, systems support the culture, and learning shows the belief. Masterful principaling is accelerating this convergence to impact student and adult learning as early as possible in the principal’s tenure. By setting culture, developing systems, and fostering the learning of all those they serve, principals create, nurture, and sustain learning organizations.30 But, what specifically is necessary for principals to do this work?

In order to fully capture what principals must do to lead learning organizations, we incorporated the National Association of Secondary School Principals’ (NASSP) new publication, Building Ranks: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective School Leaders.31 In Building Ranks, NASSP identified two critical leadership domains: culture and learning. Going further, NASSP broke each leadership domain into different dimensions, then further dissected the dimensions into concrete strategies and action steps for school leaders to consider incorporating into their own leadership.

Overall, Building Ranks provides all principals a solid leadership framework to follow as well as tangible examples from practitioners who are getting the job done in their schools. We highly recommend reading it and keeping it close by as an important resource. However, we diverged from NASSP by adding the third leadership domain of systems to our Paradigm. Our experience supporting principals with their day-to-day challenges of effectively leading and improving their learning organizations’ systems has convinced us that systems is a necessary leadership domain. But even with the addition of the systems domain to the Paradigm, the dimensions and subsequent strategies and action steps outlined in Building Ranks align well to the domains in the Paradigm.

With permission from NASSP, we deconstructed the Building Ranks dimensions aligned to the culture and learning domains. Next, we reconstructed those dimensions under our culture, systems, and learning domains. Finally, we included additional dimensions we felt were necessary to complete the Paradigm’s domains. Appendix B provides a deeper dive into the doing side of the Paradigm. A quick reference to the descriptions for the culture, systems, and learning domains and dimensions is on the next page.

For principals to be learning leaders leading learning organizations, they must recognize and understand that the interplay between becoming and doing is critical. We believe it is important for them to know which leadership attributes they should consider leveraging to conduct the concrete work their jobs require as described by the dimensions above. Therefore, Appendix C provides the alignment between the becoming and doing sides of the Paradigm. Of note, our efforts to align the two sides of the Paradigm brought to light that certain leadership attributes are necessary to conduct the work of all dimensions. Similarly, we identified three dimensions (Relationships, Vision/Mission, and Reflection/Growth) that require the use of all leadership attributes for the dimensions to be conducted well. See Appendix C for further explanation.

The research base for the leadership domains can be found here.

Culture Domain

The principal’s efforts to create, foster, and sustain a student-centered climate and culture where all adults strive to build positive and unconditional relationships with all students, while ensuring equitable access and opportunities to high-quality programs. The culture domain dimensions include:

Relationships – A focus on learners where relationships elevate experiences and outcomes that ensure optimal learning is achieved by all (Building Ranks™);

Student Centeredness – An environment where students’ needs drive the strategic alignment of organizational decisions and resources (Building Ranks™);

Wellness – An environment in which the well-being (physical, mental, and social-emotional) of everyone in the learning organization is intentionally fostered and nurtured (Building Ranks™);

Equity – The behaviors, systems, processes, resources, and environments that ensure each member of the learning organization is provided fair, just, and individualized learning and growth opportunities (Building Ranks™);

Traditions/Celebrations – The routines and procedures that elevate organizational culture as well as recognize, celebrate and honor all students, staff, and community for their achievements and service to others;

Ethics – An environment in which each person exhibits the beliefs and behaviors that uphold the universal core values that promote the learning organization’s success (Building Ranks™); and

Global Mindedness – An environment that is a microcosm of the world that navigates, engages, and reflects the richness and complexity of the global society (Building Ranks™).

Systems Domain

The principal’s efforts to assess a school’s current systems, initiate a cycle of inquiry focused on dismantling historically inequitable systems, and engage stakeholders in a collective effort to establish sustainable student-centered systems. The systems domain dimensions include:

Vision/Mission – A focus on learners where the vision inspires and sets the direction for the future and drives the mission where actions lead to outcomes (Building Ranks™);

Communication – The process used to foster collective understanding and engagement that creates and sustains a positive learning environment (Building Ranks™);

Collaborative Leadership – An environment where all members of the learning organization actively assume and support leadership for themselves and others to enhance engagement and performance (Building Ranks™);

Data Literacy – A focus on learners where all members of the learning organization understand and actively use various forms of formal and informal data to improve the learning organization;

Strategic Management – A focus on learners where school leaders align and leverage a holistic system and its processes which drive organizational performance (Building Ranks™);

Safety – An environment where the learning organization’s physical space and safety procedures are regularly monitored and maintained; and

Operations – A focus on the school operations which utilize and deploy systems that effectively balance operational efficiencies and student needs.

Learning Domain

The principal’s efforts to support the development and use of innovative practices that encourage adult and student life-long learning. The learning domain dimensions include:

Reflection/Growth – A focus on learning where introspection yields actionable feedback and strengthens the growth and productivity of the learning organization (Building Ranks™);

Result-Orientation – An environment in which everyone is accountable for the personal and collective growth of all members of the learning organization (Building Ranks™);

Curriculum – A focus on learners where content produces a high level of personal and academic achievement (Building Ranks™);

Instruction – A focus on learners where teaching methods produce a high level of personal and academic achievement (Building Ranks™);

Assessment – A focus on learners where measures produce a high level of personal and academic achievement (Building Ranks™);

Innovation – A focus on learning where creativity and risk-taking ignite a passion for learning and challenge the status quo (Building Ranks™); and

Human Capital Management – A focus on learners where the growth and development of each individual are essential to support learning and the school community (Building Ranks™).

Cycle of Inquiry

As discussed previously, we wrapped the becoming and doing sides of the Paradigm in an infinity loop (see page 5). Embedded within the loop is a cycle of inquiry, which reinforces the notion that both leaders and the learning organizations they serve should always be improving.32 The cycle is broken into four stages: 1) plan, 2) implement, 3) assess, and 4) reflect. When engaging in personal and school improvement activities, we recognize that a blending or overlapping of the four stages usually occurs. However, each deserves special attention so nothing is missed during the growth process. A brief description of the four stages is provided as follows:

Plan

The planning stage incorporates the collection and synthesis of data which school leaders must use to develop measurable goals. Additionally, resources and supports needed for school leaders to attain their identified goals should be determined;

Implement

With a comprehensive plan in place, school leaders must get to work by intentionally implementing growth initiatives. Special care must be given to monitoring the pace of implementing growth initiatives to ensure long-term sustainability;

Assess

Simply, data must be collected and reviewed to ascertain whether the growth initiatives implemented are achieving the goals identified during planning; and

Reflect

Really, school leaders should be in a constant state of reflection when it comes to growth and improvement. Not only does this help them ensure what they are doing is still relevant, but it also informs future improvement efforts.

Context

In order for the Paradigm to provide a comprehensive view of school leadership, we felt it important to accentuate a critical truth: Leadership does not exist in a vacuum. To be successful, school leaders must effectively work within a complex web of differing personalities, motivations, political connections, individual circumstances, beliefs and opinions.33 Further, school leaders have more than one contextual web to navigate at a time. In fact, they must navigate every one all of the time. Thus, we surrounded the Paradigm with four contexts (Individual, School, Community, and Political) that school leaders need to continuously monitor in order to determine how one context affects the other and how those contexts affect the leader’s ability to lead.34 Below is a brief description of each.

Individual

What happens at home matters for leaders. The quality of relationships with family and friends, personal finances, and health all impact how leaders perform;

School

Obviously, student, teacher, and parent voices are critical for school leaders to seek out and understand. However, attention must also be given to cooks, custodians, bus drivers, and anyone who engages with students;

Community

Besides being taxpayers who care about their investment in their schools, community members provide a wealth of resources, often left untapped, to support students’ learning and overall growth. Further, community members typically have strong opinions about what is happening in their schools; and

Political

School leaders must look well beyond their own home, school, and community to see everything that impacts their work. In addition to policymakers, attention must be given to the ever-changing dynamics of society as a whole.

Creating Hope

While some say hope is not a strategy, we believe the leaders who make the most indelible impact on others are effective dealers in hope This begins with the hopeful belief that all students can and will be successful, no exceptions. Hope inspires. Hope motivates. Hope solidifies trust. A leading expert on the science of hope, Dr. Shane Lopez, stated that “Hope is the leading indicator of success in relationships, academics, career, and business—as well as of a healthier, happier life.”35 Leadership that creates hope connects followers emotionally to their leader and their school. Hope-filled leaders and organizations make the impossible possible. By aligning their leadership to the Paradigm’s intelligences and domains, school leaders are provided a guide to creating hope in the people and organizations they serve.

Looking Ahead

In order for our nation’s schools to meet the needs of all kids, we as the School Leader Collaborative believe every child in every school deserves a high-quality principal. Every child. Right now. But if we want to ensure every child has a high-quality principal leading their school, we as a nation must possess a greater sense of urgency to develop and support principals across the country. Otherwise, we will not be able to reduce the alarming rate of principal churn which negatively impacts our ability to attract and retain teachers, maximize adult and student performance, close achievement gaps, and guarantee equitable educational opportunities for all students.

To this end, the School Leader Collaborative is committed to using our collective capacity to develop and support all school leaders to help them get better faster and stay in positions longer. We will use the School Leader Paradigm to focus and guide our efforts to create the resources and professional learning supports for individuals whether they be aspiring leaders, first-year launching leaders, growing as building leaders, or reaching the pinnacle of the profession as mastering leaders. Further, we will use the Paradigm to engage school district leaders, preparation programs, policymakers, and the public with a common vision and language about what makes a principal effective and what is necessary to support and sustain our nation’s principals. Overall, we will use the Paradigm as a source of hope-filled conviction needed to ensure all of our schools’ leaders are learning leaders leading learning organizations.

The School Leader Collaborative

The School Leader Collaborative (the Collaborative) consists of a consortium of state principal associations dedicated to supporting and sustaining the professional growth of school principals and their leadership teams. Specifically, the Collaborative enhances the collective capacity of its partner associations by building a network of shared resources, innovative best practices, and research, which supports school leaders throughout their careers. Current Collaborative associations are:

Acknowledgement

The School Leader Paradigm: Becoming While Doing, incorporates the National Association of Secondary School Principals’ (NASSP) new publication, Building Ranks: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective School Leaders. NASSP granted permission for the Collaborative to use the Building Ranks™ materials. Building Ranks™ describes the essential leadership skills of building culture and leading learning that contribute to a school environment conducive for preparing the whole child for success in the global community. We highly recommend reading and using Building Ranks™ as an important resource. Please visit www.nassp.org/buildingranks for additional information. Permission to use the Building Ranks™ materials can be obtained by contacting NASSP at professionallearning@nassp.org.

Endnotes

1. United States Congress, Senate Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity. (1970). Toward equal educational opportunity. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

2. Maxwell, J. (1999). The 21 indispensable qualities of a leader. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, Inc.

3. Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great. New York: HarperCollins Publishing, Inc.

4. Wallace Foundation. (2009). Assessing the effectiveness of school leaders: New directions and new processes. Retrieved from http://wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Assessing-the-Effectiveness-of-School-Leaders.pdf

5. Branch, G., Hanushek, E. & Rivkin, S. (2013). School leaders matter: Measuring the impact of effective principals. Education Next, 13(1), 62-69.; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92-109.; Leithwood, K., Seashore Louis, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). Review of research: How leadership influences student learning. Center for Applied Research and Education, University of Minnesota. Retrieved from http://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/2035; Waters, T., Marzano, R., & McNulty, B. (2003). Balanced leadership: What 30 years of research tells us about the effect of leadership on student achievement. A working paper. Aurora, CO: Mid-Continent Research for Education and Learning.

6. Branch, G., Hanushek, E. & Rivkin, S. (2013)

7. Branch, G., Hanushek, E. & Rivkin, S. (2013); Burkhauser, S. (2016). How much do principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/teacherbeat/Study.pdf; Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2007). High poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from http://www.caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/1001057_High_Poverty.pdf; TNTP. (2012). The irreplaceables: Understanding the real retention crisis in American’s urban schools. Retrieved from http://tntp.org/publications/view/retention-and-school-culture/the-irreplaceables-understanding-the-real-retention-crisis

8. Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2009). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions (CALDER Working Paper No. 25). Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publications-pdfs/1001287-The-Influence-of-School-Administrators-on-Teacher-Retention-Decisions.pdf; Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr, M., & Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from exemplary leadership development programs. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute. Retrieved from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/school-leadership/key-research/Documents/Preparing-School-Leaders.pdf; Marinell, W., & Coca, V. (2013). Who stays and who leaves: Findings from a three-part study of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools. New York, NY: New York University, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development, Research Alliance for New York City Schools. Retrieved from https:///steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/media/users/sg158/PDFs/ttp_synthesis/TTPSynthesis_ExecutiveSummary_March2013.pdf; Scholastic. (2010). Primary sources: America’s teachers on America’s schools. A project of Scholastic and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.scholastic.com/primarysources/pdfs/Scholastic_Gates_0310.pdf

9. Mendels, P. (2012). The effective principals, JSD, 33(1) 54-58. Oxford, OH: Learning Forward. Retrieved from http://glisi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/The-Effective-Principal_JSD.pdf

10. Goldring, E., Porter, A., Murphy, J., Stephen, N. E., & Cravens, X. (2009). Assessing learning-centered leadership: Connections to research, professional standards, and current practices. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(1), 1-36. doi:10.1080/15700760802014951; Thompson, T. G., & Barnes, R. E. (2007). Beyond NCLB: Fulfilling the promise to our nation’s children. Washington, D.C.: Aspen Institute.

11. The Wallace Foundation. (2013). The school principal as leader: Guiding schools to better teaching and learning. Retrieved from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/The-School-Principal-as-Leader-Guiding-Schools-to-Better-Teaching-and-Learning-2nd-Ed.pdf

12. School Leaders Network. (2014). Churn: The high cost of principal turnover. Retrieved from http://connectleadsucceed.org/sites/default/files/principal_turnover_cost.pdf

13. Johnson, L. (2005). Why principals quit. Principal. National Association of Elementary School Principals.; Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. (2013). The MetLife Survey of the American Teacher: Challenges for school leadership. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved fromhttps://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/foundation/MetLife-Teacher-Survey-2012.pdf

14. School Leaders Network. (2014)

15. Beteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2011). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Working Paper Series (17243).

16. Rowalnd, C. (2017). Principal professional development: New opportunities for a renewed state focus. Washington, D.C.: American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/ downloads/report/Principal-Professional- Development-New-Opportunities-State-Focus-February-2017.pdf

17. Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

18. School Leaders Network. (2014)

19. Fullan, M. (2014) The principal: Three keys to maximizing impact. San Francisco, CA:Jossey-Bass.; Northouse, P. G. (2010). Leadership: Theory and practice, 5th Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

20. Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2001, December). Primal Leadership: The Hidden Driver of Great Performance. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

21. Mayer, J. D. (2014). Personal Intelligence: The Power of personality and How It Shapes Our Lives, New York, NY: Macmillan.

22. Goleman, D. (2007). Social Intelligence. New York: Random House.

23. Hämäläinen, R. & Saarinen, E. (2007). Essays on Systems Intelligence. Espoo: Aalto University, School of Science and Technology, Systems Analysis Laboratory, 9-26.

24. Billings, J. and Carlson, D. (2016) Promising Practices in Boosting School Leadership Capacity: Principal Academies. Washington, D.C.: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices; Sun, M., Youngs, P., Yang, H., Chu, H., & Zhao, Q. (2012). Association of district principal evaluation with learning-centered leadership practice: Evidence from Michigan and Beijing. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 24(3), 189-213. doi:10.1007/s11092-012-9145-7

25. Bethman, J. L. (2015). The principal evaluation process: Principals’ learning as a result of the evaluation process (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2376/5468; Franks, L. E. (2015). A Q methodology study: Components of principal evaluation systems as perceived by Alabama educational leaders (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama; Kutash, J., Nico E., Gorin, E., Rahmatullah, S., & Tallant, K. (2010). The school turnaround field guide. Boston, MA: FSG Social Impact Advisors.

26. Wallace Foundation. (2018). Federal funding and the four turnaround models – The school turnaround field guide. Retrieved from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/federal-funding-school-turnaround-field-guide.aspx

27. National Policy Board for Educational Administration. (2015). Professional Standards for Educational Leaders 2015. Reston, VA: Author.

28. Karhuse, A. (2016). A historic day for students, teachers, and principals as the senate votes to replace NCLB. Retrieved from http://blog.nassp.org/2015/12/09/a-historic-day-for-students-teachers-and-principals-as-the-senate-votes-to-replace-nclb/

29. School Leaders Network. (2014)

30. Council of Chief State School Officers. (2008). Educational leadership policy standards: 2008 ISLLC. Washington, DC: CCSSO; Dean, C., Hubbell, E., Pitler, H., & Stone, B. (2012). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement (2nd edition). Alexandria, VA: ASCD; Fullan, M. (2014) The principal: Three keys to maximizing impact. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2014). Using Student Test Scores to Measure Principal Performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; National Policy Board for Educational Administration. (2015)

31. National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP). (2018). Building Ranks: A comprehensive framework for effective school leaders © NASSP, Reston, VA. All Rights Reserved. Permission to use must be granted by NASSP. Please send permission requests toprofessionallearning@nassp.org.

32. Fullan, M. (2005). Leadership and Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

33. Costa, A. & Kallick, B., eds. (2008). Learning and Leading with Habits of Mind: 16 Essential Characteristics for Success. Alexandria, VA: ASCD; Sergiovanni, T. (2007). Rethinking Leadership, 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

34. Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.

35. University of Minnesota. (2019). The science of hope: An interview with Shane Lopez. Retrieved from https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/science-hope-interview-shane-lopez

Aspiring

Aspiring Launching

Launching Building

Building Mastering

Mastering